Atom

| Helium atom | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||

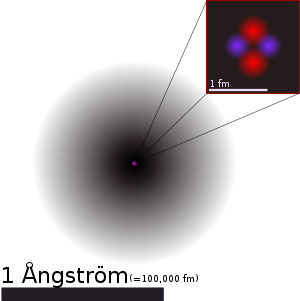

| An illustration of the helium atom, depicting the nucleus (pink) and the electron cloud distribution (black). The nucleus (upper right) in helium-4 is in reality spherically symmetric and closely resembles the electron cloud, although for more complicated nuclei this is not always the case. The black bar is one ångström, equal to 10−10 m or 100,000 fm. | ||||||||

| Classification | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Properties | ||||||||

|

The atom is a basic unit of matter that consists of a dense, central nucleus surrounded by a cloud of negatively charged electrons. The atomic nucleus contains a mix of positively charged protons and electrically neutral neutrons (except in the case of hydrogen-1, which is the only stable nuclide with no neutrons). The electrons of an atom are bound to the nucleus by the electromagnetic force. Likewise, a group of atoms can remain bound to each other, forming a molecule. An atom containing an equal number of protons and electrons is electrically neutral, otherwise it has a positive or negative charge and is an ion. An atom is classified according to the number of protons and neutrons in its nucleus: the number of protons determines the chemical element, and the number of neutrons determines the isotope of the element.[1]

The name atom comes from the Greek "ἄτομος"—átomos (from α-, "un-" + τέμνω - temno, "to cut"[2]), which means uncuttable, or indivisible, something that cannot be divided further.[3] The concept of an atom as an indivisible component of matter was first proposed by early Indian and Greek philosophers. In the 17th and 18th centuries, chemists provided a physical basis for this idea by showing that certain substances could not be further broken down by chemical methods. During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, physicists discovered subatomic components and structure inside the atom, thereby demonstrating that the 'atom' was divisible. The principles of quantum mechanics were used to successfully model the atom.[4][5]

Atoms are minuscule objects with proportionately tiny masses. Atoms can only be observed individually using special instruments such as the scanning tunneling microscope. Over 99.9% of an atom's mass is concentrated in the nucleus,[note 1] with protons and neutrons having roughly equal mass. Each element has at least one isotope with unstable nuclei that can undergo radioactive decay. This can result in a transmutation that changes the number of protons or neutrons in a nucleus.[6] Electrons that are bound to atoms possess a set of stable energy levels, or orbitals, and can undergo transitions between them by absorbing or emitting photons that match the energy differences between the levels. The electrons determine the chemical properties of an element, and strongly influence an atom's magnetic properties.

Contents |

History

Atomism

The concept that matter is composed of discrete units and cannot be divided into arbitrarily tiny quantities has been around for millennia, but these ideas were founded in abstract, philosophical reasoning rather than experimentation and empirical observation. The nature of atoms in philosophy varied considerably over time and between cultures and schools, and often had spiritual elements. Nevertheless, the basic idea of the atom was adopted by scientists thousands of years later because it elegantly explained new discoveries in the field of chemistry.[7]

The earliest references to the concept of atoms date back to ancient India in the 6th century BCE,[8] appearing first in Jainism.[9] The Nyaya and Vaisheshika schools developed elaborate theories of how atoms combined into more complex objects.[10] In the West, the references to atoms emerged a century later from Leucippus, whose student, Democritus, systematized his views. In approximately 450 BCE, Democritus coined the term átomos (Greek: ἄτομος), which means "uncuttable" or "the smallest indivisible particle of matter". Although the Indian and Greek concepts of the atom were based purely on philosophy, modern science has retained the name coined by Democritus.[7]

Corpuscularianism is the postulate, expounded in the 13th-century by the alchemist Pseudo-Geber (Geber),[11] sometimes identified with Paul of Taranto, that all physical bodies possess an inner and outer layer of minute particles or corpuscles.[12] Corpuscularianism is similar to the theory atomism, except that where atoms were supposed to be indivisible, corpuscles could in principle be divided. In this manner, for example, it was theorized that mercury could penetrate into metals and modify their inner structure.[13] Corpuscularianism stayed a dominant theory over the next several hundred years.

In 1661, natural philosopher Robert Boyle published The Sceptical Chymist in which he argued that matter was composed of various combinations of different "corpuscules" or atoms, rather than the classical elements of air, earth, fire and water.[14] During the 1670s was used by Isaac Newton in his development of the corpuscular theory of light.[12][15]

Origin of scientific theory

Further progress in the understanding of atoms did not occur until the science of chemistry began to develop. In 1789, French nobleman and scientific researcher Antoine Lavoisier discovered the law of conservation of mass and defined an element as a basic substance that could not be further broken down by the methods of chemistry.[16]

In 1803, English instructor and natural philosopher John Dalton used the concept of atoms to explain why elements always react in ratios of small whole numbers (the law of multiple proportions) and why certain gases dissolve better in water than others. He proposed that each element consists of atoms of a single, unique type, and that these atoms can join together to form chemical compounds.[17][18] Dalton is considered the originator of modern atomic theory.[19]

Additional validation of particle theory (and by extension atomic theory) occurred in 1827 when botanist Robert Brown used a microscope to look at dust grains floating in water and discovered that they moved about erratically—a phenomenon that became known as "Brownian motion". J. Desaulx suggested in 1877 that the phenomenon was caused by the thermal motion of water molecules, and in 1905 Albert Einstein produced the first mathematical analysis of the motion.[20][21][22] French physicist Jean Perrin used Einstein's work to experimentally determine the mass and dimensions of atoms, thereby conclusively verifying Dalton's atomic theory.[23]

In 1869, building upon earlier discoveries by such scientists as Lavoisier, Dmitri Mendeleev published the first functional periodic table.[24] The table itself is a visual representation of the periodic law, which states that certain chemical properties of elements repeat periodically when arranged by atomic number.[25]

Subcomponents and quantum theory

The physicist J. J. Thomson, through his work on cathode rays in 1897, discovered the electron, and concluded that they were a component of every atom. Thus he overturned the belief that atoms are the indivisible, ultimate particles of matter.[26] Thomson postulated that the low mass, negatively charged electrons were distributed throughout the atom, possibly rotating in rings, with their charge balanced by the presence of a uniform sea of positive charge. This later became known as the plum pudding model.

In 1909, Hans Geiger and Ernest Marsden, under the direction of physicist Ernest Rutherford, bombarded a sheet of gold foil with alpha rays—by then known to be positively charged helium atoms—and discovered that a small percentage of these particles were deflected through much larger angles than was predicted using Thomson's proposal. Rutherford interpreted the gold foil experiment as suggesting that the positive charge of a heavy gold atom and most of its mass was concentrated in a nucleus at the center of the atom—the Rutherford model.[27]

While experimenting with the products of radioactive decay, in 1913 radiochemist Frederick Soddy discovered that there appeared to be more than one type of atom at each position on the periodic table.[28] The term isotope was coined by Margaret Todd as a suitable name for different atoms that belong to the same element. J.J. Thomson created a technique for separating atom types through his work on ionized gases, which subsequently led to the discovery of stable isotopes.[29]

Meanwhile, in 1913, physicist Niels Bohr suggested that the electrons were confined into clearly defined, quantized orbits, and could jump between these, but could not freely spiral inward or outward in intermediate states.[30] An electron must absorb or emit specific amounts of energy to transition between these fixed orbits. When the light from a heated material was passed through a prism, it produced a multi-colored spectrum. The appearance of fixed lines in this spectrum was successfully explained by these orbital transitions.[31]

Chemical bonds between atoms were now explained, by Gilbert Newton Lewis in 1916, as the interactions between their constituent electrons.[32] As the chemical properties of the elements were known to largely repeat themselves according to the periodic law,[33] in 1919 the American chemist Irving Langmuir suggested that this could be explained if the electrons in an atom were connected or clustered in some manner. Groups of electrons were thought to occupy a set of electron shells about the nucleus.[34]

The Stern–Gerlach experiment of 1922 provided further evidence of the quantum nature of the atom. When a beam of silver atoms was passed through a specially shaped magnetic field, the beam was split based on the direction of an atom's angular momentum, or spin. As this direction is random, the beam could be expected to spread into a line. Instead, the beam was split into two parts, depending on whether the atomic spin was oriented up or down.[35]

In 1924, Louis de Broglie proposed that all particles behave to an extent like waves. In 1926, Erwin Schrödinger used this idea to develop a mathematical model of the atom that described the electrons as three-dimensional waveforms rather than point particles. A consequence of using waveforms to describe particles is that it is mathematically impossible to obtain precise values for both the position and momentum of a particle at the same time; this became known as the uncertainty principle, formulated by Werner Heisenberg in 1926. In this concept, for a given accuracy in measuring a position one could only obtain a range of probable values for momentum, and vice versa. This model was able to explain observations of atomic behavior that previous models could not, such as certain structural and spectral patterns of atoms larger than hydrogen. Thus, the planetary model of the atom was discarded in favor of one that described atomic orbital zones around the nucleus where a given electron is most likely to be observed.[36][37]

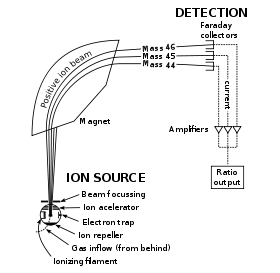

The development of the mass spectrometer allowed the exact mass of atoms to be measured. The device uses a magnet to bend the trajectory of a beam of ions, and the amount of deflection is determined by the ratio of an atom's mass to its charge. The chemist Francis William Aston used this instrument to show that isotopes had different masses. The atomic mass of these isotopes varied by integer amounts, called the whole number rule.[38] The explanation for these different isotopes awaited the discovery of the neutron, a neutral-charged particle with a mass similar to the proton, by the physicist James Chadwick in 1932. Isotopes were then explained as elements with the same number of protons, but different numbers of neutrons within the nucleus.[39]

Fission, high energy physics and condensed matter

In 1938, the German chemist Otto Hahn, a student of Rutherford, directed neutrons onto uranium atoms expecting to get transuranium elements. Instead, his chemical experiments showed barium as a product.[40] A year later, Lise Meitner and her nephew Otto Frisch verified that Hahn's result were the first experimental nuclear fission.[41][42] In 1944, Hahn received the Nobel prize in chemistry. Despite Hahn's efforts, the contributions of Meitner and Frisch were not recognized.[43]

In the 1950s, the development of improved particle accelerators and particle detectors allowed scientists to study the impacts of atoms moving at high energies.[44] Neutrons and protons were found to be hadrons, or composites of smaller particles called quarks. Standard models of nuclear physics were developed that successfully explained the properties of the nucleus in terms of these sub-atomic particles and the forces that govern their interactions.[45]

Components

Subatomic particles

Though the word atom originally denoted a particle that cannot be cut into smaller particles, in modern scientific usage the atom is composed of various subatomic particles. The constituent particles of an atom are the electron, the proton and the neutron. However, the hydrogen-1 atom has no neutrons and a positive hydrogen ion has no electrons.

The electron is by far the least massive of these particles at 9.11 × 10−31 kg, with a negative electrical charge and a size that is too small to be measured using available techniques.[46] Protons have a positive charge and a mass 1,836 times that of the electron, at 1.6726 × 10−27 kg, although this can be reduced by changes to the energy binding the proton into an atom. Neutrons have no electrical charge and have a free mass of 1,839 times the mass of electrons,[47] or 1.6929 × 10−27 kg. Neutrons and protons have comparable dimensions—on the order of 2.5 × 10−15 m—although the 'surface' of these particles is not sharply defined.[48]

In the Standard Model of physics, both protons and neutrons are composed of elementary particles called quarks. The quark belongs to the fermion group of particles, and is one of the two basic constituents of matter—the other being the lepton, of which the electron is an example. There are six types of quarks, each having a fractional electric charge of either +2/3 or −1/3. Protons are composed of two up quarks and one down quark, while a neutron consists of one up quark and two down quarks. This distinction accounts for the difference in mass and charge between the two particles. The quarks are held together by the strong nuclear force, which is mediated by gluons. The gluon is a member of the family of gauge bosons, which are elementary particles that mediate physical forces.[49][50]

Nucleus

All the bound protons and neutrons in an atom make up a tiny atomic nucleus, and are collectively called nucleons. The radius of a nucleus is approximately equal to ![\begin{smallmatrix}1.07 \sqrt[3]{A}\end{smallmatrix}](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/70dc2ced9f84c7b142a9e1105af95744.png) fm, where A is the total number of nucleons.[51] This is much smaller than the radius of the atom, which is on the order of 105 fm. The nucleons are bound together by a short-ranged attractive potential called the residual strong force. At distances smaller than 2.5 fm this force is much more powerful than the electrostatic force that causes positively charged protons to repel each other.[52]

fm, where A is the total number of nucleons.[51] This is much smaller than the radius of the atom, which is on the order of 105 fm. The nucleons are bound together by a short-ranged attractive potential called the residual strong force. At distances smaller than 2.5 fm this force is much more powerful than the electrostatic force that causes positively charged protons to repel each other.[52]

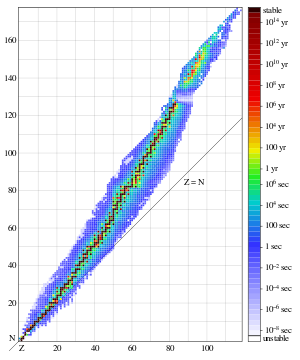

Atoms of the same element have the same number of protons, called the atomic number. Within a single element, the number of neutrons may vary, determining the isotope of that element. The total number of protons and neutrons determine the nuclide. The number of neutrons relative to the protons determines the stability of the nucleus, with certain isotopes undergoing radioactive decay.[53]

The neutron and the proton are different types of fermions. The Pauli exclusion principle is a quantum mechanical effect that prohibits identical fermions, such as multiple protons, from occupying the same quantum physical state at the same time. Thus every proton in the nucleus must occupy a different state, with its own energy level, and the same rule applies to all of the neutrons. This prohibition does not apply to a proton and neutron occupying the same quantum state.[54]

For atoms with low atomic numbers, a nucleus that has a different number of protons than neutrons can potentially drop to a lower energy state through a radioactive decay that causes the number of protons and neutrons to more closely match. As a result, atoms with roughly matching numbers of protons and neutrons are more stable against decay. However, with increasing atomic number, the mutual repulsion of the protons requires an increasing proportion of neutrons to maintain the stability of the nucleus, which modifies this trend. Thus, there are no stable nuclei with equal proton and neutron numbers above atomic number Z = 20 (calcium); and as Z increases toward the heaviest nuclei, the ratio of neutrons per proton required for stability increases to about 1.5.[54]

The number of protons and neutrons in the atomic nucleus can be modified, although this can require very high energies because of the strong force. Nuclear fusion occurs when multiple atomic particles join to form a heavier nucleus, such as through the energetic collision of two nuclei. For example, at the core of the Sun protons require energies of 3–10 keV to overcome their mutual repulsion—the coulomb barrier—and fuse together into a single nucleus.[55] Nuclear fission is the opposite process, causing a nucleus to split into two smaller nuclei—usually through radioactive decay. The nucleus can also be modified through bombardment by high energy subatomic particles or photons. If this modifies the number of protons in a nucleus, the atom changes to a different chemical element.[56][57]

If the mass of the nucleus following a fusion reaction is less than the sum of the masses of the separate particles, then the difference between these two values can be emitted as a type of usable energy (such as a gamma ray, or the kinetic energy of a beta particle), as described by Albert Einstein's mass–energy equivalence formula, E = mc2, where m is the mass loss and c is the speed of light. This deficit is part of the binding energy of the new nucleus, and it is the non-recoverable loss of the energy that causes the fused particles to remain together in a state that requires this energy to separate.[58]

The fusion of two nuclei that create larger nuclei with lower atomic numbers than iron and nickel—a total nucleon number of about 60—is usually an exothermic process that releases more energy than is required to bring them together.[59] It is this energy-releasing process that makes nuclear fusion in stars a self-sustaining reaction. For heavier nuclei, the binding energy per nucleon in the nucleus begins to decrease. That means fusion processes producing nuclei that have atomic numbers higher than about 26, and atomic masses higher than about 60, is an endothermic process. These more massive nuclei can not undergo an energy-producing fusion reaction that can sustain the hydrostatic equilibrium of a star.[54]

Electron cloud

The electrons in an atom are attracted to the protons in the nucleus by the electromagnetic force. This force binds the electrons inside an electrostatic potential well surrounding the smaller nucleus, which means that an external source of energy is needed for the electron to escape. The closer an electron is to the nucleus, the greater the attractive force. Hence electrons bound near the center of the potential well require more energy to escape than those at greater separations.

Electrons, like other particles, have properties of both a particle and a wave. The electron cloud is a region inside the potential well where each electron forms a type of three-dimensional standing wave—a wave form that does not move relative to the nucleus. This behavior is defined by an atomic orbital, a mathematical function that characterises the probability that an electron appears to be at a particular location when its position is measured.[60] Only a discrete (or quantized) set of these orbitals exist around the nucleus, as other possible wave patterns rapidly decay into a more stable form.[61] Orbitals can have one or more ring or node structures, and they differ from each other in size, shape and orientation.[62]

Each atomic orbital corresponds to a particular energy level of the electron. The electron can change its state to a higher energy level by absorbing a photon with sufficient energy to boost it into the new quantum state. Likewise, through spontaneous emission, an electron in a higher energy state can drop to a lower energy state while radiating the excess energy as a photon. These characteristic energy values, defined by the differences in the energies of the quantum states, are responsible for atomic spectral lines.[61]

The amount of energy needed to remove or add an electron—the electron binding energy—is far less than the binding energy of nucleons. For example, it requires only 13.6 eV to strip a ground-state electron from a hydrogen atom,[63] compared to 2.23 million eV for splitting a deuterium nucleus.[64] Atoms are electrically neutral if they have an equal number of protons and electrons. Atoms that have either a deficit or a surplus of electrons are called ions. Electrons that are farthest from the nucleus may be transferred to other nearby atoms or shared between atoms. By this mechanism, atoms are able to bond into molecules and other types of chemical compounds like ionic and covalent network crystals.[65]

Properties

Nuclear properties

By definition, any two atoms with an identical number of protons in their nuclei belong to the same chemical element. Atoms with equal numbers of protons but a different number of neutrons are different isotopes of the same element. For example, all hydrogen atoms admit exactly one proton, but isotopes exist with no neutrons hydrogen-1, one neutron (deuterium), two neutrons (tritium) and more than two neutrons. The hydrogen-1 is by far the most common form, and is sometimes called protium.[66] The known elements form a set of atomic numbers from hydrogen with a single proton up to the 118-proton element ununoctium.[67] All known isotopes of elements with atomic numbers greater than 82 are radioactive.[68][69]

About 339 nuclides occur naturally on Earth,[70] of which 227 (about 67%) have not been observed to decay, and are referred to as "stable isotopes". However, only 90 of these nuclides are stable to all decay, even in theory. About 30 more (bringing the total to 257) have been observed to decay, but have half lives too long to be estimated. These are also often classified as "stable." An additional 31 radioactive nuclides have half lives longer than 80 million years, and are thus long-lived enough to be present from the birth of the solar system. This collection of 288 nuclides are known as primordial nuclides. Finally, an additional 51 short-lived nuclides are known to occur naturally, as daughter products of primordial nuclide decay (such as radium from uranium), or else as products of natural energetic processes on Earth, such as cosmic ray bombardment (for example, carbon-14).[71][72].

For 80 of the chemical elements, at least one stable isotope exists. Elements 43, 61, and all elements numbered 83 or higher have no stable isotopes. As a rule, there is, for each element, only a handful of stable isotopes, the average being 3.1 stable isotopes per element among those that have stable isotopes. Twenty-seven elements have only a single stable isotope, while the largest number of stable isotopes observed for any element is ten, for the element tin.[73]

Stability of isotopes is affected by the ratio of protons to neutrons, and also by the presence of certain "magic numbers" of neutrons or protons that represent closed and filled quantum shells. These quantum shells correspond to a set of energy levels within the shell model of the nucleus; filled shells, such as the filled shell of 50 protons for tin, confers unusual stability on the nuclide. Of the 256 known stable nuclides, only four have both an odd number of protons and odd number of neutrons: hydrogen-2 (deuterium), lithium-6, boron-10 and nitrogen-14. Also, only four naturally occurring, radioactive odd-odd nuclides have a half-life over a billion years: potassium-40, vanadium-50, lanthanum-138 and tantalum-180m. Most odd-odd nuclei are highly unstable with respect to beta decay, because the decay products are even-even, and are therefore more strongly bound, due to nuclear pairing effects.[73]

Mass

The large majority of an atom's mass comes from the protons and neutrons, the total number of these particles in an atom is called the mass number. The mass of an atom at rest is often expressed using the unified atomic mass unit (u), which is also called a Dalton (Da). This unit is defined as a twelfth of the mass of a free neutral atom of carbon-12, which is approximately 1.66 × 10−27 kg.[74] Hydrogen-1, the lightest isotope of hydrogen and the atom with the lowest mass, has an atomic weight of 1.007825 u.[75] An atom has a mass approximately equal to the mass number times the atomic mass unit.[76] The heaviest stable atom is lead-208,[68] with a mass of 207.9766521 u.[77]

As even the most massive atoms are far too light to work with directly, chemists instead use the unit of moles. The mole is defined such that one mole of any element always has the same number of atoms (about 6.022 × 1023). This number was chosen so that if an element has an atomic mass of 1 u, a mole of atoms of that element has a mass close to 0.001 kg, or 1 gram. Because of the definition of the unified atomic mass unit, carbon has an atomic mass of exactly 12 u, and so a mole of carbon atoms weighs exactly 0.012 kg.[74]

Shape and size

Atoms lack a well-defined outer boundary, so their dimensions are usually described in terms of an atomic radius. This is a measure of the distance out to which the electron cloud extends from the nucleus. However, this assumes the atom to exhibit a spherical shape, which is only obeyed for atoms in vacuum or free space. Atomic radii may be derived from the distances between two nuclei when the two atoms are joined in a chemical bond. The radius varies with the location of an atom on the atomic chart, the type of chemical bond, the number of neighboring atoms (coordination number) and a quantum mechanical property known as spin.[78] On the periodic table of the elements, atom size tends to increase when moving down columns, but decrease when moving across rows (left to right).[79] Consequently, the smallest atom is helium with a radius of 32 pm, while one of the largest is caesium at 225 pm.[80]

When subjected to external fields, like an electrical field, the shape of an atom may deviate from that a sphere. The deformation depends on the field magnitude and the orbital type of outer shell electrons, as shown by group-theoretical considerations. Aspherical deviations might be elicited for instance in crystals, where large crystal-electrical fields may occur at low-symmetry lattice sites.[81]. Significant ellipsoidal deformations have recently been shown to occur for sulfur ions in pyrite-type compounds [82]

Atomic dimensions are thousands of times smaller than the wavelengths of light (400–700 nm) so they can not be viewed using an optical microscope. However, individual atoms can be observed using a scanning tunneling microscope. To visualize the minuteness of the atom, consider that a typical human hair is about 1 million carbon atoms in width.[83] A single drop of water contains about 2 sextillion (2 × 1021) atoms of oxygen, and twice the number of hydrogen atoms.[84] A single carat diamond with a mass of 2 × 10-4 kg contains about 10 sextillion (1022) atoms of carbon.[note 2] If an apple were magnified to the size of the Earth, then the atoms in the apple would be approximately the size of the original apple.[85]

Radioactive decay

Every element has one or more isotopes that have unstable nuclei that are subject to radioactive decay, causing the nucleus to emit particles or electromagnetic radiation. Radioactivity can occur when the radius of a nucleus is large compared with the radius of the strong force, which only acts over distances on the order of 1 fm.[86]

The most common forms of radioactive decay are:[87][88]

- Alpha decay is caused when the nucleus emits an alpha particle, which is a helium nucleus consisting of two protons and two neutrons. The result of the emission is a new element with a lower atomic number.

- Beta decay is regulated by the weak force, and results from a transformation of a neutron into a proton, or a proton into a neutron. The first is accompanied by the emission of an electron and an antineutrino, while the second causes the emission of a positron and a neutrino. The electron or positron emissions are called beta particles. Beta decay either increases or decreases the atomic number of the nucleus by one.

- Gamma decay results from a change in the energy level of the nucleus to a lower state, resulting in the emission of electromagnetic radiation. This can occur following the emission of an alpha or a beta particle from radioactive decay.

Other more rare types of radioactive decay include ejection of neutrons or protons or clusters of nucleons from a nucleus, or more than one beta particle, or result (through internal conversion) in production of high-speed electrons that are not beta rays, and high-energy photons that are not gamma rays.

Each radioactive isotope has a characteristic decay time period—the half-life—that is determined by the amount of time needed for half of a sample to decay. This is an exponential decay process that steadily decreases the proportion of the remaining isotope by 50% every half life. Hence after two half-lives have passed only 25% of the isotope is present, and so forth.[86]

Magnetic moment

Elementary particles possess an intrinsic quantum mechanical property known as spin. This is analogous to the angular momentum of an object that is spinning around its center of mass, although strictly speaking these particles are believed to be point-like and cannot be said to be rotating. Spin is measured in units of the reduced Planck constant (ħ), with electrons, protons and neutrons all having spin ½ ħ, or "spin-½". In an atom, electrons in motion around the nucleus possess orbital angular momentum in addition to their spin, while the nucleus itself possesses angular momentum due to its nuclear spin.[89]

The magnetic field produced by an atom—its magnetic moment—is determined by these various forms of angular momentum, just as a rotating charged object classically produces a magnetic field. However, the most dominant contribution comes from spin. Due to the nature of electrons to obey the Pauli exclusion principle, in which no two electrons may be found in the same quantum state, bound electrons pair up with each other, with one member of each pair in a spin up state and the other in the opposite, spin down state. Thus these spins cancel each other out, reducing the total magnetic dipole moment to zero in some atoms with even number of electrons.[90]

In ferromagnetic elements such as iron, an odd number of electrons leads to an unpaired electron and a net overall magnetic moment. The orbitals of neighboring atoms overlap and a lower energy state is achieved when the spins of unpaired electrons are aligned with each other, a process known as an exchange interaction. When the magnetic moments of ferromagnetic atoms are lined up, the material can produce a measurable macroscopic field. Paramagnetic materials have atoms with magnetic moments that line up in random directions when no magnetic field is present, but the magnetic moments of the individual atoms line up in the presence of a field.[90][91]

The nucleus of an atom can also have a net spin. Normally these nuclei are aligned in random directions because of thermal equilibrium. However, for certain elements (such as xenon-129) it is possible to polarize a significant proportion of the nuclear spin states so that they are aligned in the same direction—a condition called hyperpolarization. This has important applications in magnetic resonance imaging.[92][93]

Energy levels

When an electron is bound to an atom, it has a potential energy that is inversely proportional to its distance from the nucleus. This is measured by the amount of energy needed to unbind the electron from the atom, and is usually given in units of electronvolts (eV). In the quantum mechanical model, a bound electron can only occupy a set of states centered on the nucleus, and each state corresponds to a specific energy level. The lowest energy state of a bound electron is called the ground state, while an electron at a higher energy level is in an excited state.[94]

For an electron to transition between two different states, it must absorb or emit a photon at an energy matching the difference in the potential energy of those levels. The energy of an emitted photon is proportional to its frequency, so these specific energy levels appear as distinct bands in the electromagnetic spectrum.[95] Each element has a characteristic spectrum that can depend on the nuclear charge, subshells filled by electrons, the electromagnetic interactions between the electrons and other factors.[96]

When a continuous spectrum of energy is passed through a gas or plasma, some of the photons are absorbed by atoms, causing electrons to change their energy level. Those excited electrons that remain bound to their atom spontaneously emit this energy as a photon, traveling in a random direction, and so drop back to lower energy levels. Thus the atoms behave like a filter that forms a series of dark absorption bands in the energy output. (An observer viewing the atoms from a view that doesn't include the continuous spectrum in the background, instead sees a series of emission lines from the photons emitted by the atoms.) Spectroscopic measurements of the strength and width of spectral lines allow the composition and physical properties of a substance to be determined.[97]

Close examination of the spectral lines reveals that some display a fine structure splitting. This occurs because of spin-orbit coupling, which is an interaction between the spin and motion of the outermost electron.[98] When an atom is in an external magnetic field, spectral lines become split into three or more components; a phenomenon called the Zeeman effect. This is caused by the interaction of the magnetic field with the magnetic moment of the atom and its electrons. Some atoms can have multiple electron configurations with the same energy level, which thus appear as a single spectral line. The interaction of the magnetic field with the atom shifts these electron configurations to slightly different energy levels, resulting in multiple spectral lines.[99] The presence of an external electric field can cause a comparable splitting and shifting of spectral lines by modifying the electron energy levels, a phenomenon called the Stark effect.[100]

If a bound electron is in an excited state, an interacting photon with the proper energy can cause stimulated emission of a photon with a matching energy level. For this to occur, the electron must drop to a lower energy state that has an energy difference matching the energy of the interacting photon. The emitted photon and the interacting photon then move off in parallel and with matching phases. That is, the wave patterns of the two photons are synchronized. This physical property is used to make lasers, which can emit a coherent beam of light energy in a narrow frequency band.[101]

Valence and bonding behavior

The outermost electron shell of an atom in its uncombined state is known as the valence shell, and the electrons in that shell are called valence electrons. The number of valence electrons determines the bonding behavior with other atoms. Atoms tend to chemically react with each other in a manner that fills (or empties) their outer valence shells.[102] For example, a transfer of a single electron between atoms is a useful approximation for bonds that form between atoms with one-electron more than a filled shell, and others that are one-electron short of a full shell, such as occurs in the compound sodium chloride and other chemical ionic salts. However, many elements display multiple valences, or tendencies to share differing numbers of electrons in different compounds. Thus, chemical bonding between these elements takes many forms of electron-sharing that are more than simple electron transfers. Examples include the element carbon and the organic compounds.[103]

The chemical elements are often displayed in a periodic table that is laid out to display recurring chemical properties, and elements with the same number of valence electrons form a group that is aligned in the same column of the table. (The horizontal rows correspond to the filling of a quantum shell of electrons.) The elements at the far right of the table have their outer shell completely filled with electrons, which results in chemically inert elements known as the noble gases.[104][105]

States

Quantities of atoms are found in different states of matter that depend on the physical conditions, such as temperature and pressure. By varying the conditions, materials can transition between solids, liquids, gases and plasmas.[106] Within a state, a material can also exist in different phases. An example of this is solid carbon, which can exist as graphite or diamond.[107]

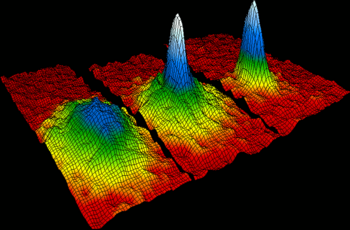

At temperatures close to absolute zero, atoms can form a Bose–Einstein condensate, at which point quantum mechanical effects, which are normally only observed at the atomic scale, become apparent on a macroscopic scale.[108][109] This super-cooled collection of atoms then behaves as a single super atom, which may allow fundamental checks of quantum mechanical behavior.[110]

Identification

The scanning tunneling microscope is a device for viewing surfaces at the atomic level. It uses the quantum tunneling phenomenon, which allows particles to pass through a barrier that would normally be insurmountable. Electrons tunnel through the vacuum between two planar metal electrodes, on each of which is an adsorbed atom, providing a tunneling-current density that can be measured. Scanning one atom (taken as the tip) as it moves past the other (the sample) permits plotting of tip displacement versus lateral separation for a constant current. The calculation shows the extent to which scanning-tunneling-microscope images of an individual atom are visible. It confirms that for low bias, the microscope images the space-averaged dimensions of the electron orbitals across closely packed energy levels—the Fermi level local density of states.[111][112]

An atom can be ionized by removing one of its electrons. The electric charge causes the trajectory of an atom to bend when it passes through a magnetic field. The radius by which the trajectory of a moving ion is turned by the magnetic field is determined by the mass of the atom. The mass spectrometer uses this principle to measure the mass-to-charge ratio of ions. If a sample contains multiple isotopes, the mass spectrometer can determine the proportion of each isotope in the sample by measuring the intensity of the different beams of ions. Techniques to vaporize atoms include inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy and inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry, both of which use a plasma to vaporize samples for analysis.[113]

A more area-selective method is electron energy loss spectroscopy, which measures the energy loss of an electron beam within a transmission electron microscope when it interacts with a portion of a sample. The atom-probe tomograph has sub-nanometer resolution in 3-D and can chemically identify individual atoms using time-of-flight mass spectrometry.[114]

Spectra of excited states can be used to analyze the atomic composition of distant stars. Specific light wavelengths contained in the observed light from stars can be separated out and related to the quantized transitions in free gas atoms. These colors can be replicated using a gas-discharge lamp containing the same element.[115] Helium was discovered in this way in the spectrum of the Sun 23 years before it was found on Earth.[116]

Origin and current state

Atoms form about 4% of the total energy density of the observable universe, with an average density of about 0.25 atoms/m3.[117] Within a galaxy such as the Milky Way, atoms have a much higher concentration, with the density of matter in the interstellar medium (ISM) ranging from 105 to 109 atoms/m3.[118] The Sun is believed to be inside the Local Bubble, a region of highly ionized gas, so the density in the solar neighborhood is only about 103 atoms/m3.[119] Stars form from dense clouds in the ISM, and the evolutionary processes of stars result in the steady enrichment of the ISM with elements more massive than hydrogen and helium. Up to 95% of the Milky Way's atoms are concentrated inside stars and the total mass of atoms forms about 10% of the mass of the galaxy.[120] (The remainder of the mass is an unknown dark matter.[121])

Nucleosynthesis

Stable protons and electrons appeared one second after the Big Bang. During the following three minutes, Big Bang nucleosynthesis produced most of the helium, lithium, and deuterium in the universe, and perhaps some of the beryllium and boron.[122][123][124] The first atoms (complete with bound electrons) were theoretically created 380,000 years after the Big Bang—an epoch called recombination, when the expanding universe cooled enough to allow electrons to become attached to nuclei.[125] Since then, atomic nuclei have been combined in stars through the process of nuclear fusion to produce elements up to iron.[126]

Isotopes such as lithium-6 are generated in space through cosmic ray spallation.[127] This occurs when a high-energy proton strikes an atomic nucleus, causing large numbers of nucleons to be ejected. Elements heavier than iron were produced in supernovae through the r-process and in AGB stars through the s-process, both of which involve the capture of neutrons by atomic nuclei.[128] Elements such as lead formed largely through the radioactive decay of heavier elements.[129]

Earth

Most of the atoms that make up the Earth and its inhabitants were present in their current form in the nebula that collapsed out of a molecular cloud to form the Solar System. The rest are the result of radioactive decay, and their relative proportion can be used to determine the age of the Earth through radiometric dating.[130][131] Most of the helium in the crust of the Earth (about 99% of the helium from gas wells, as shown by its lower abundance of helium-3) is a product of alpha decay.[132]

There are a few trace atoms on Earth that were not present at the beginning (i.e., not "primordial"), nor are results of radioactive decay. Carbon-14 is continuously generated by cosmic rays in the atmosphere.[133] Some atoms on Earth have been artificially generated either deliberately or as by-products of nuclear reactors or explosions.[134][135] Of the transuranic elements—those with atomic numbers greater than 92—only plutonium and neptunium occur naturally on Earth.[136][137] Transuranic elements have radioactive lifetimes shorter than the current age of the Earth[138] and thus identifiable quantities of these elements have long since decayed, with the exception of traces of plutonium-244 possibly deposited by cosmic dust.[130] Natural deposits of plutonium and neptunium are produced by neutron capture in uranium ore.[139]

The Earth contains approximately 1.33 × 1050 atoms.[140] In the planet's atmosphere, small numbers of independent atoms of noble gases exist, such as argon and neon. The remaining 99% of the atmosphere is bound in the form of molecules, including carbon dioxide and diatomic oxygen and nitrogen. At the surface of the Earth, atoms combine to form various compounds, including water, salt, silicates and oxides. Atoms can also combine to create materials that do not consist of discrete molecules, including crystals and liquid or solid metals.[141][142] This atomic matter forms networked arrangements that lack the particular type of small-scale interrupted order associated with molecular matter.[143]

Rare and theoretical forms

While isotopes with atomic numbers higher than lead (82) are known to be radioactive, an "island of stability" has been proposed for some elements with atomic numbers above 103. These superheavy elements may have a nucleus that is relatively stable against radioactive decay.[144] The most likely candidate for a stable superheavy atom, unbihexium, has 126 protons and 184 neutrons.[145]

Each particle of matter has a corresponding antimatter particle with the opposite electrical charge. Thus, the positron is a positively charged antielectron and the antiproton is a negatively charged equivalent of a proton. When a matter and corresponding antimatter particle meet, they annihilate each other. Because of this, along with an imbalance between the number of matter and antimatter particles, the latter are rare in the universe. (The first causes of this imbalance are not yet fully understood, although the baryogenesis theories may offer an explanation.) As a result, no antimatter atoms have been discovered in nature.[146][147] However, in 1996, antihydrogen, the antimatter counterpart of hydrogen, was synthesized at the CERN laboratory in Geneva.[148][149]

Other exotic atoms have been created by replacing one of the protons, neutrons or electrons with other particles that have the same charge. For example, an electron can be replaced by a more massive muon, forming a muonic atom. These types of atoms can be used to test the fundamental predictions of physics.[150][151][152]

See also

|

|

Notes

- ↑ Most isotopes have more nucleons than electrons. In the case of hydrogen-1, with a single electron and nucleon, the proton is

, or 99.95% of the total atomic mass.

, or 99.95% of the total atomic mass. - ↑ A carat is 200 milligrams. By definition, carbon-12 has 0.012 kg per mole. The Avogadro constant defines 6 × 1023 atoms per mole.

References

- ↑ Leigh, G. J., ed (1990). International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry, Commission on the Nomenclature of Inorganic Chemistry, Nomenclature of Organic Chemistry - Recommendations 1990. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Publications. p. 35. ISBN 0-08-022369-9. "An atom is the smallest unit quantity of an element that is capable of existence whether alone or in chemical combination with other atoms of the same or other elements."

- ↑ Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert. "A Greek-English Lexicon". Perseus Digital Library. http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.04.0057%3Aentry%3Dte%2Fmnw1.

- ↑ Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert. "ἄτομος". A Greek-English Lexicon. Perseus Digital Library. http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.04.0057%3Aentry%3Da%29%2Ftomos. Retrieved 2010-06-21.

- ↑ Haubold, Hans; Mathai, A.M. (1998). "Microcosmos: From Leucippus to Yukawa". Structure of the Universe. http://www.columbia.edu/~ah297/unesa/universe/universe-chapter3.html. Retrieved 2008-01-17.

- ↑ Harrison (2003:123–139).

- ↑ "Radioactive Decays". Stanford Linear Accelerator Center. 15 June 2009. http://www2.slac.stanford.edu/vvc/theory/nuclearstability.html. Retrieved 2009-07-04.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Ponomarev (1993:14–15).

- ↑ Gangopadhyaya (1981).

- ↑ Iannone (2001:62).

- ↑ Teresi (2003:213–214).

- ↑ Moran (2005:146).

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Levere (2001:7)

- ↑ Pratt, Vernon (28 September 2007). "The Mechanical Philosophy". Reason, nature and the human being in the West. http://www.vernonpratt.com/conceptualisations/d06bl2_1mechanical.htm. Retrieved 2009-06-28.

- ↑ Siegfried (2002:42–55).

- ↑ Kemerling, Garth (8 August 2002). "Corpuscularianism". Philosophical Dictionary. http://www.philosophypages.com/dy/c9.htm. Retrieved 2009-06-17.

- ↑ "Lavoisier's Elements of Chemistry". Elements and Atoms. Le Moyne College, Department of Chemistry. http://web.lemoyne.edu/~GIUNTA/EA/LAVPREFann.HTML. Retrieved 2007-12-18.

- ↑ Wurtz (1881:1–2).

- ↑ Dalton (1808).

- ↑ Patterson, Elizabeth C. (1970). John Dalton and the Atomic Theory. Garden City, New York: Anchor.

- ↑ Einstein, Albert (1905). "Über die von der molekularkinetischen Theorie der Wärme geforderte Bewegung von in ruhenden Flüssigkeiten suspendierten Teilchen" (in German) (PDF). Annalen der Physik 322 (8): 549–560. doi:10.1002/andp.19053220806. http://www.zbp.univie.ac.at/dokumente/einstein2.pdf. Retrieved 2007-02-04.

- ↑ Mazo (2002:1–7).

- ↑ Lee, Y.K.; Hoon, K. (1995). "Brownian Motion". Imperial College. http://www.doc.ic.ac.uk/~nd/surprise_95/journal/vol4/ykl/report.html. Retrieved 2007-12-18.

- ↑ Patterson, G. (2007). "Jean Perrin and the triumph of the atomic doctrine". Endeavour 31 (2): 50–53. doi:10.1016/j.endeavour.2007.05.003. PMID 17602746. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17602746.

- ↑ "Periodic Table of the Elements". The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry. November 1, 2007. http://old.iupac.org/reports/periodic_table/. Retrieved 2010-05-14.

- ↑ Scerri (2007:10–17).

- ↑ "J.J. Thomson". Nobel Foundation. 1906. http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/physics/laureates/1906/thomson-bio.html. Retrieved 2007-12-20.

- ↑ Rutherford, E. (1911). "The Scattering of α and β Particles by Matter and the Structure of the Atom". Philosophical Magazine 21: 669–88. http://ion.elte.hu/~akos/orak/atfsz/atom/rutherford_atom11.pdf.

- ↑ "Frederick Soddy, The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1921". Nobel Foundation. http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/chemistry/laureates/1921/soddy-bio.html. Retrieved 2008-01-18.

- ↑ Thomson, Joseph John (1913). "Rays of positive electricity". Proceedings of the Royal Society A 89: 1–20. http://web.lemoyne.edu/~giunta/canal.html.

- ↑ Stern, David P. (16 May 2005). "The Atomic Nucleus and Bohr's Early Model of the Atom". NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center. http://www-spof.gsfc.nasa.gov/stargaze/Q5.htm. Retrieved 2007-12-20.

- ↑ Bohr, Neils (11 December 1922). "Niels Bohr, The Nobel Prize in Physics 1922, Nobel Lecture". Nobel Foundation. http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/physics/laureates/1922/bohr-lecture.html. Retrieved 2008-02-16.

- ↑ Lewis, Gilbert N. (1916). "The Atom and the Molecule". Journal of the American Chemical Society 38 (4): 762–786. doi:10.1021/ja02261a002.

- ↑ Scerri (2007:205–226)

- ↑ Langmuir, Irving (1919). "The Arrangement of Electrons in Atoms and Molecules". Journal of the American Chemical Society 41 (6): 868–934. doi:10.1021/ja02227a002.

- ↑ Scully, Marlan O.; Lamb, Willis E.; Barut, Asim (1987). "On the theory of the Stern-Gerlach apparatus". Foundations of Physics 17 (6): 575–583. doi:10.1007/BF01882788.

- ↑ Brown, Kevin (2007). "The Hydrogen Atom". MathPages. http://www.mathpages.com/home/kmath538/kmath538.htm. Retrieved 2007-12-21.

- ↑ Harrison, David M. (2000). "The Development of Quantum Mechanics". University of Toronto. http://www.upscale.utoronto.ca/GeneralInterest/Harrison/DevelQM/DevelQM.html. Retrieved 2007-12-21.

- ↑ Aston, Francis W. (1920). "The constitution of atmospheric neon". Philosophical Magazine 39 (6): 449–55.

- ↑ Chadwick, James (12 December 1935). "Nobel Lecture: The Neutron and Its Properties". Nobel Foundation. http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/physics/laureates/1935/chadwick-lecture.html. Retrieved 2007-12-21.

- ↑ "Otto Hahn, Lise Meitner and Fritz Strassmann". Chemical Achievers: The Human Face of the Chemical Sciences. Chemical Heritage Foundation. http://www.chemheritage.org/classroom/chemach/atomic/hahn-meitner.html. Retrieved 2009-09-15.

- ↑ Meitner, Lise; Frisch, Otto Robert (1939). "Disintegration of uranium by neutrons: a new type of nuclear reaction". Nature 143: 239. doi:10.1038/143239a0.

- ↑ Schroeder, M.. "Lise Meitner - Zur 125. Wiederkehr Ihres Geburtstages" (in German). http://www.physik3.gwdg.de/~mrs/Vortraege/Lise_Meitner-Vortrag-20031106/. Retrieved 2009-06-04.

- ↑ Crawford, E.; Sime, Ruth Lewin; Walker, Mark (1997). "A Nobel tale of postwar injustice". Physics Today 50 (9): 26–32. doi:10.1063/1.881933. http://md1.csa.com/partners/viewrecord.php?requester=gs&collection=TRD&recid=63212AN&q=A+Nobel+tale+of+postwar+injustice&uid=787269344&setcookie=yes.

- ↑ Kullander, Sven (28 August 2001). "Accelerators and Nobel Laureates". Nobel Foundation. http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/physics/articles/kullander/. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ↑ "The Nobel Prize in Physics 1990". Nobel Foundation. 17 October 1990. http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/physics/laureates/1990/press.html. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ↑ Demtröder (2002:39–42).

- ↑ Woan (2000:8).

- ↑ MacGregor (1992:33–37).

- ↑ Particle Data Group (2002). "The Particle Adventure". Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory. http://www.particleadventure.org/. Retrieved 2007-01-03.

- ↑ Schombert, James (April 18, 2006). "Elementary Particles". University of Oregon. http://abyss.uoregon.edu/~js/ast123/lectures/lec07.html. Retrieved 2007-01-03.

- ↑ Jevremovic (2005:63).

- ↑ Pfeffer (2000:330–336).

- ↑ Wenner, Jennifer M. (October 10, 2007). "How Does Radioactive Decay Work?". Carleton College. http://serc.carleton.edu/quantskills/methods/quantlit/RadDecay.html. Retrieved 2008-01-09.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 54.2 Raymond, David (April 7, 2006). "Nuclear Binding Energies". New Mexico Tech. http://physics.nmt.edu/~raymond/classes/ph13xbook/node216.html. Retrieved 2007-01-03.

- ↑ Mihos, Chris (July 23, 2002). "Overcoming the Coulomb Barrier". Case Western Reserve University. http://burro.cwru.edu/Academics/Astr221/StarPhys/coulomb.html. Retrieved 2008-02-13.

- ↑ Staff (March 30, 2007). "ABC's of Nuclear Science". Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. http://www.lbl.gov/abc/Basic.html. Retrieved 2007-01-03.

- ↑ Makhijani, Arjun; Saleska, Scott (March 2, 2001). "Basics of Nuclear Physics and Fission". Institute for Energy and Environmental Research. http://www.ieer.org/reports/n-basics.html. Retrieved 2007-01-03.

- ↑ Shultis et al. (2002:72–6).

- ↑ Fewell, M. P. (1995). "The atomic nuclide with the highest mean binding energy". American Journal of Physics 63 (7): 653–58. doi:10.1119/1.17828. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1995AmJPh..63..653F. Retrieved 2007-02-01.

- ↑ Mulliken, Robert S. (1967). "Spectroscopy, Molecular Orbitals, and Chemical Bonding". Science 157 (3784): 13–24. doi:10.1126/science.157.3784.13. PMID 5338306.

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 Brucat, Philip J. (2008). "The Quantum Atom". University of Florida. http://www.chem.ufl.edu/~itl/2045/lectures/lec_10.html. Retrieved 2007-01-04.

- ↑ Manthey, David (2001). "Atomic Orbitals". Orbital Central. http://www.orbitals.com/orb/. Retrieved 2008-01-21.

- ↑ Herter, Terry (2006). "Lecture 8: The Hydrogen Atom". Cornell University. http://astrosun2.astro.cornell.edu/academics/courses/astro101/herter/lectures/lec08.htm. Retrieved 2008-02-14.

- ↑ Bell, R. E.; Elliott, L. G. (1950). "Gamma-Rays from the Reaction H1(n,γ)D2 and the Binding Energy of the Deuteron". Physical Review 79 (2): 282–285. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.79.282.

- ↑ Smirnov (2003:249–72).

- ↑ Matis, Howard S. (August 9, 2000). "The Isotopes of Hydrogen". Guide to the Nuclear Wall Chart. Lawrence Berkeley National Lab. http://www.lbl.gov/abc/wallchart/chapters/02/3.html. Retrieved 2007-12-21.

- ↑ Weiss, Rick (October 17, 2006). "Scientists Announce Creation of Atomic Element, the Heaviest Yet". Washington Post. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2006/10/16/AR2006101601083.html. Retrieved 2007-12-21.

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 Sills (2003:131–134).

- ↑ Dumé, Belle (April 23, 2003). "Bismuth breaks half-life record for alpha decay". Physics World. http://physicsworld.com/cws/article/news/17319. Retrieved 2007-12-21.

- ↑ Lindsay, Don (July 30, 2000). "Radioactives Missing From The Earth". Don Lindsay Archive. http://www.don-lindsay-archive.org/creation/isotope_list.html. Retrieved 2007-05-23.

- ↑ Jagdish K. Tuli, Nuclear Wallet Cards, 7th edition, April 2005, Brookhaven National Laboratory, US National Nuclear Data Center

- ↑ For more recent updates see Interactive Chart of Nuclides (Brookhaven National Laboratory)

- ↑ 73.0 73.1 CRC Handbook (2002).

- ↑ 74.0 74.1 Mills et al. (1993).

- ↑ Chieh, Chung (January 22, 2001). "Nuclide Stability". University of Waterloo. http://www.science.uwaterloo.ca/~cchieh/cact/nuctek/nuclideunstable.html. Retrieved 2007-01-04.

- ↑ "Atomic Weights and Isotopic Compositions for All Elements". National Institute of Standards and Technology. http://physics.nist.gov/cgi-bin/Compositions/stand_alone.pl?ele=&ascii=html&isotype=some. Retrieved 2007-01-04.

- ↑ Audi, G. (2003). "The Ame2003 atomic mass evaluation (II)". Nuclear Physics A 729: 337–676. doi:10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2003.11.003. http://www.nndc.bnl.gov/amdc/web/masseval.html. Retrieved 2008-02-07.

- ↑ Shannon, R. D. (1976). "Revised effective ionic radii and systematic studies of interatomic distances in halides and chalcogenides". Acta Crystallographica, Section a 32: 751. doi:10.1107/S0567739476001551. http://journals.iucr.org/a/issues/1976/05/00/issconts.html. Retrieved 2007-01-03.

- ↑ Dong, Judy (1998). "Diameter of an Atom". The Physics Factbook. http://hypertextbook.com/facts/MichaelPhillip.shtml. Retrieved 2007-11-19.

- ↑ Zumdahl (2002).

- ↑ Bethe, H. (1929). "Termaufspaltung in Kristallen". Annalen der Physik, 5. Folge 3: 133.

- ↑ Birkholz, M.; Rudert, R. (2008). "Interatomic distances in pyrite-structure disulfides – a case for ellipsoidal modeling of sulfur ions". Physica status solidi b 245: 1858. doi:10.1002/pssb.200879532. http://www.mariobirkholz.de/pssb2008.pdf.

- ↑ Staff (2007). "Small Miracles: Harnessing nanotechnology". Oregon State University. http://oregonstate.edu/terra/2007winter/features/nanotech.php. Retrieved 2007-01-07.—describes the width of a human hair as 105 nm and 10 carbon atoms as spanning 1 nm.

- ↑ Padilla et al. (2002:32)—"There are 2,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 (that's 2 sextillion) atoms of oxygen in one drop of water—and twice as many atoms of hydrogen."

- ↑ Feynman (1995).

- ↑ 86.0 86.1 "Radioactivity". Splung.com. http://www.splung.com/content/sid/5/page/radioactivity. Retrieved 2007-12-19.

- ↑ L'Annunziata (2003:3–56).

- ↑ Firestone, Richard B. (May 22, 2000). "Radioactive Decay Modes". Berkeley Laboratory. http://isotopes.lbl.gov/education/decmode.html. Retrieved 2007-01-07.

- ↑ Hornak, J. P. (2006). "Chapter 3: Spin Physics". The Basics of NMR. Rochester Institute of Technology. http://www.cis.rit.edu/htbooks/nmr/chap-3/chap-3.htm. Retrieved 2007-01-07.

- ↑ 90.0 90.1 Schroeder, Paul A. (February 25, 2000). "Magnetic Properties". University of Georgia. http://www.gly.uga.edu/schroeder/geol3010/magnetics.html. Retrieved 2007-01-07.

- ↑ Goebel, Greg (September 1, 2007). "[4.3] Magnetic Properties of the Atom". Elementary Quantum Physics. In The Public Domain website. http://www.vectorsite.net/tpqm_04.html. Retrieved 2007-01-07.

- ↑ Yarris, Lynn (Spring 1997). "Talking Pictures". Berkeley Lab Research Review. http://www.lbl.gov/Science-Articles/Research-Review/Magazine/1997/story1.html. Retrieved 2008-01-09.

- ↑ Liang and Haacke (1999:412–26).

- ↑ Zeghbroeck, Bart J. Van (1998). "Energy levels". Shippensburg University. http://physics.ship.edu/~mrc/pfs/308/semicon_book/eband2.htm. Retrieved 2007-12-23.

- ↑ Fowles (1989:227–233).

- ↑ Martin, W. C.; Wiese, W. L. (May 2007). "Atomic Spectroscopy: A Compendium of Basic Ideas, Notation, Data, and Formulas". National Institute of Standards and Technology. http://physics.nist.gov/Pubs/AtSpec/. Retrieved 2007-01-08.

- ↑ "Atomic Emission Spectra — Origin of Spectral Lines". Avogadro Web Site. http://www.avogadro.co.uk/light/bohr/spectra.htm. Retrieved 2006-08-10.

- ↑ Fitzpatrick, Richard (February 16, 2007). "Fine structure". University of Texas at Austin. http://farside.ph.utexas.edu/teaching/qm/lectures/node55.html. Retrieved 2008-02-14.

- ↑ Weiss, Michael (2001). "The Zeeman Effect". University of California-Riverside. http://math.ucr.edu/home/baez/spin/node8.html. Retrieved 2008-02-06.

- ↑ Beyer (2003:232–236).

- ↑ Watkins, Thayer. "Coherence in Stimulated Emission". San José State University. http://www.sjsu.edu/faculty/watkins/stimem.htm. Retrieved 2007-12-23.

- ↑ Reusch, William (July 16, 2007). "Virtual Textbook of Organic Chemistry". Michigan State University. http://www.cem.msu.edu/~reusch/VirtualText/intro1.htm. Retrieved 2008-01-11.

- ↑ "Covalent bonding - Single bonds". chemguide. 2000. http://www.chemguide.co.uk/atoms/bonding/covalent.html.

- ↑ Husted, Robert et al. (December 11, 2003). "Periodic Table of the Elements". Los Alamos National Laboratory. http://periodic.lanl.gov/default.htm. Retrieved 2008-01-11.

- ↑ Baum, Rudy (2003). "It's Elemental: The Periodic Table". Chemical & Engineering News. http://pubs.acs.org/cen/80th/elements.html. Retrieved 2008-01-11.

- ↑ Goodstein (2002:436–438).

- ↑ Brazhkin, Vadim V. (2006). "Metastable phases, phase transformations, and phase diagrams in physics and chemistry". Physics-Uspekhi 49: 719–24. doi:10.1070/PU2006v049n07ABEH006013.

- ↑ Myers (2003:85).

- ↑ Staff (October 9, 2001). "Bose-Einstein Condensate: A New Form of Matter". National Institute of Standards and Technology. http://www.nist.gov/public_affairs/releases/BEC_background.htm. Retrieved 2008-01-16.

- ↑ Colton, Imogen; Fyffe, Jeanette (February 3, 1999). "Super Atoms from Bose-Einstein Condensation". The University of Melbourne. http://www.ph.unimelb.edu.au/~ywong/poster/articles/bec.html. Retrieved 2008-02-06.

- ↑ Jacox, Marilyn; Gadzuk, J. William (November 1997). "Scanning Tunneling Microscope". National Institute of Standards and Technology. http://physics.nist.gov/GenInt/STM/stm.html. Retrieved 2008-01-11.

- ↑ "The Nobel Prize in Physics 1986". The Nobel Foundation. http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/physics/laureates/1986/index.html. Retrieved 2008-01-11.—in particular, see the Nobel lecture by G. Binnig and H. Rohrer.

- ↑ Jakubowski, N. (1998). "Sector field mass spectrometers in ICP-MS". Spectrochimica Acta Part B: Atomic Spectroscopy 53 (13): 1739–63. doi:10.1016/S0584-8547(98)00222-5.

- ↑ Müller, Erwin W.; Panitz, John A.; McLane, S. Brooks (1968). "The Atom-Probe Field Ion Microscope". Review of Scientific Instruments 39 (1): 83–86. doi:10.1063/1.1683116. ISSN 0034-6748.

- ↑ Lochner, Jim; Gibb, Meredith; Newman, Phil (April 30, 2007). "What Do Spectra Tell Us?". NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center. http://imagine.gsfc.nasa.gov/docs/science/how_l1/spectral_what.html. Retrieved 2008-01-03.

- ↑ Winter, Mark (2007). "Helium". WebElements. http://www.webelements.com/webelements/elements/text/He/hist.html. Retrieved 2008-01-03.

- ↑ Hinshaw, Gary (February 10, 2006). "What is the Universe Made Of?". NASA/WMAP. http://map.gsfc.nasa.gov/m_uni/uni_101matter.html. Retrieved 2008-01-07.

- ↑ Choppin et al. (2001).

- ↑ Davidsen, Arthur F. (1993). "Far-Ultraviolet Astronomy on the Astro-1 Space Shuttle Mission". Science 259 (5093): 327–34. doi:10.1126/science.259.5093.327. PMID 17832344. http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/abstract/259/5093/327. Retrieved 2008-01-07.

- ↑ Lequeux (2005:4).

- ↑ Smith, Nigel (January 6, 2000). "The search for dark matter". Physics World. http://physicsworld.com/cws/article/print/809. Retrieved 2008-02-14.

- ↑ Croswell, Ken (1991). "Boron, bumps and the Big Bang: Was matter spread evenly when the Universe began? Perhaps not; the clues lie in the creation of the lighter elements such as boron and beryllium". New Scientist (1794): 42. http://space.newscientist.com/article/mg13217944.700-boron-bumps-and-the-big-bang-was-matter-spread-evenly-whenthe-universe-began-perhaps-not-the-clues-lie-in-the-creation-of-thelighter-elements-such-as-boron-and-beryllium.html. Retrieved 2008-01-14.

- ↑ Copi, Craig J.; Schramm, DN; Turner, MS (1995). "Big-Bang Nucleosynthesis and the Baryon Density of the Universe" (PDF). Science 267 (5195): 192–99. doi:10.1126/science.7809624. PMID 7809624. http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/reprint/267/5195/192.pdf. Retrieved 2008-01-13.

- ↑ Hinshaw, Gary (December 15, 2005). "Tests of the Big Bang: The Light Elements". NASA/WMAP. http://map.gsfc.nasa.gov/m_uni/uni_101bbtest2.html. Retrieved 2008-01-13.

- ↑ Abbott, Brian (May 30, 2007). "Microwave (WMAP) All-Sky Survey". Hayden Planetarium. http://www.haydenplanetarium.org/universe/duguide/exgg_wmap.php. Retrieved 2008-01-13.

- ↑ F. Hoyle (1946). "The synthesis of the elements from hydrogen". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 106: 343–83. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1946MNRAS.106..343H. Retrieved 2008-01-13.

- ↑ Knauth, D. C.; Knauth, D. C.; Lambert, David L.; Crane, P. (2000). "Newly synthesized lithium in the interstellar medium". Nature 405 (6787): 656–58. doi:10.1038/35015028. PMID 10864316.

- ↑ Mashnik, Stepan G. (August 2000). "On Solar System and Cosmic Rays Nucleosynthesis and Spallation Processes". Cornell University. http://arxiv.org/abs/astro-ph/0008382. Retrieved 2008-01-14.

- ↑ Kansas Geological Survey (May 4, 2005). "Age of the Earth". University of Kansas. http://www.kgs.ku.edu/Extension/geotopics/earth_age.html. Retrieved 2008-01-14.

- ↑ 130.0 130.1 Manuel (2001:407–430,511–519).

- ↑ Dalrymple, G. Brent (2001). "The age of the Earth in the twentieth century: a problem (mostly) solved". Geological Society, London, Special Publications 190: 205–21. doi:10.1144/GSL.SP.2001.190.01.14. http://sp.lyellcollection.org/cgi/content/abstract/190/1/205. Retrieved 2008-01-14.

- ↑ Anderson, Don L.; Foulger, G. R.; Meibom, Anders (September 2, 2006). "Helium: Fundamental models". MantlePlumes.org. http://www.mantleplumes.org/HeliumFundamentals.html. Retrieved 2007-01-14.

- ↑ Pennicott, Katie (May 10, 2001). "Carbon clock could show the wrong time". PhysicsWeb. http://physicsworld.com/cws/article/news/2676. Retrieved 2008-01-14.

- ↑ Yarris, Lynn (July 27, 2001). "New Superheavy Elements 118 and 116 Discovered at Berkeley Lab". Berkeley Lab. http://enews.lbl.gov/Science-Articles/Archive/elements-116-118.html. Retrieved 2008-01-14.

- ↑ Diamond, H; Fields, P. R.; Stevens, C. S.; Studier, M. H.; Fried, S. M.; Inghram, M. G.; Hess, D. C.; Pyle, G. L. et al. (1960). "Heavy Isotope Abundances in Mike Thermonuclear Device" (subscription required). Physical Review 119: 2000–04. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.119.2000. http://prola.aps.org/abstract/PR/v119/i6/p2000_1. Retrieved 2008-01-14.

- ↑ Poston Sr., John W. (March 23, 1998). "Do transuranic elements such as plutonium ever occur naturally?". Scientific American. http://www.sciam.com/chemistry/article/id/do-transuranic-elements-s/topicID/4/catID/3. Retrieved 2008-01-15.

- ↑ Keller, C. (1973). "Natural occurrence of lanthanides, actinides, and superheavy elements". Chemiker Zeitung 97 (10): 522–30. http://www.osti.gov/energycitations/product.biblio.jsp?osti_id=4353086. Retrieved 2008-01-15.

- ↑ Marco (2001:17).

- ↑ "Oklo Fossil Reactors". Curtin University of Technology. http://www.oklo.curtin.edu.au/index.cfm. Retrieved 2008-01-15.

- ↑ Weisenberger, Drew. "How many atoms are there in the world?". Jefferson Lab. http://education.jlab.org/qa/mathatom_05.html. Retrieved 2008-01-16.

- ↑ Pidwirny, Michael. "Fundamentals of Physical Geography". University of British Columbia Okanagan. http://www.physicalgeography.net/fundamentals/contents.html. Retrieved 2008-01-16.

- ↑ Anderson, Don L. (2002). "The inner inner core of Earth". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 99 (22): 13966–68. doi:10.1073/pnas.232565899. PMID 12391308. PMC 137819. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=137819. Retrieved 2008-01-16.

- ↑ Pauling (1960:5–10).

- ↑ Anonymous (October 2, 2001). "Second postcard from the island of stability". CERN Courier. http://cerncourier.com/cws/article/cern/28509. Retrieved 2008-01-14.

- ↑ Jacoby, Mitch (2006). "As-yet-unsynthesized superheavy atom should form a stable diatomic molecule with fluorine". Chemical & Engineering News 84 (10): 19. http://pubs.acs.org/cen/news/84/i10/8410notw9.html. Retrieved 2008-01-14.

- ↑ Koppes, Steve (March 1, 1999). "Fermilab Physicists Find New Matter-Antimatter Asymmetry". University of Chicago. http://www-news.uchicago.edu/releases/99/990301.ktev.shtml. Retrieved 2008-01-14.

- ↑ Cromie, William J. (August 16, 2001). "A lifetime of trillionths of a second: Scientists explore antimatter". Harvard University Gazette. http://www.hno.harvard.edu/gazette/2001/08.16/antimatter.html. Retrieved 2008-01-14.

- ↑ Hijmans, Tom W. (2002). "Particle physics: Cold antihydrogen". Nature 419 (6906): 439–40. doi:10.1038/419439a. PMID 12368837.

- ↑ Staff (October 30, 2002). "Researchers 'look inside' antimatter". BBC News. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/2375717.stm. Retrieved 2008-01-14.

- ↑ Barrett, Roger (1990). "The Strange World of the Exotic Atom". New Scientist (1728): 77–115. http://media.newscientist.com/article/mg12717284.600-the-strange-world-of-the-exotic-atom-physicists-can-nowmake-atoms-and-molecules-containing-negative-particles-other-than-electronsand-use-them-not-just-to-test-theories-but-also-to-fight-cancer-.html. Retrieved 2008-01-04.

- ↑ Indelicato, Paul (2004). "Exotic Atoms". Physica Scripta T112: 20–26. doi:10.1238/Physica.Topical.112a00020.

- ↑ Ripin, Barrett H. (July 1998). "Recent Experiments on Exotic Atoms". American Physical Society. http://www.aps.org/publications/apsnews/199807/experiment.cfm.html. Retrieved 2008-02-15.

Book references

- L'Annunziata, Michael F. (2003). Handbook of Radioactivity Analysis. Academic Press. ISBN 0124366031. OCLC 162129551.

- Beyer, H. F.; Shevelko, V. P. (2003). Introduction to the Physics of Highly Charged Ions. CRC Press. ISBN 0750304812. OCLC 47150433.

- Choppin, Gregory R.; Liljenzin, Jan-Olov; Rydberg, Jan (2001). Radiochemistry and Nuclear Chemistry. Elsevier. ISBN 0750674636. OCLC 162592180.

- Dalton, J. (1808). A New System of Chemical Philosophy, Part 1. London and Manchester: S. Russell.

- Demtröder, Wolfgang (2002). Atoms, Molecules and Photons: An Introduction to Atomic- Molecular- and Quantum Physics (1st ed.). Springer. ISBN 3540206310. OCLC 181435713.

- Feynman, Richard (1995). Six Easy Pieces. The Penguin Group. ISBN 978-0-140-27666-4. OCLC 40499574.

- Fowles, Grant R. (1989). Introduction to Modern Optics. Courier Dover Publications. ISBN 0486659577. OCLC 18834711.

- Gangopadhyaya, Mrinalkanti (1981). Indian Atomism: History and Sources. Atlantic Highlands, New Jersey: Humanities Press. ISBN 0-391-02177-X. OCLC 10916778.

- Goodstein, David L. (2002). States of Matter. Courier Dover Publications. ISBN 048649506X. ISBN 013843557X.

- Harrison, Edward Robert (2003). Masks of the Universe: Changing Ideas on the Nature of the Cosmos. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521773512. OCLC 50441595.

- Iannone, A. Pablo (2001). Dictionary of World Philosophy. Routledge. ISBN 0415179955. OCLC 44541769.

- Jevremovic, Tatjana (2005). Nuclear Principles in Engineering. Springer. ISBN 0387232842. OCLC 228384008.

- Lequeux, James (2005). The Interstellar Medium. Springer. ISBN 3540213260. OCLC 133157789.

- Levere, Trevor, H. (2001). Transforming Matter – A History of Chemistry for Alchemy to the Buckyball. The Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-6610-3.

- Liang, Z.-P.; Haacke, E. M. (1999). Webster, J. G.. ed (PDF). Encyclopedia of Electrical and Electronics Engineering: Magnetic Resonance Imaging. vol. 2. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 412–26. ISBN 0471139467. http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/iel5/8734/27658/01233976.pdf?arnumber=1233976. Retrieved 2008-01-09.

- MacGregor, Malcolm H. (1992). The Enigmatic Electron. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195218337. OCLC 223372888.

- Manuel, Oliver (2001). Origin of Elements in the Solar System: Implications of Post-1957 Observations. Springer. ISBN 0306465620. OCLC 228374906.

- Mazo, Robert M. (2002). Brownian Motion: Fluctuations, Dynamics, and Applications. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198515677. OCLC 48753074.

- Mills, Ian; Cvitaš, Tomislav; Homann, Klaus; Kallay, Nikola; Kuchitsu, Kozo (1993). Quantities, Units and Symbols in Physical Chemistry (2nd ed.). Oxford: International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry, Commission on Physiochemical Symbols Terminology and Units, Blackwell Scientific Publications. ISBN 0-632-03583-8. OCLC 27011505.

- Moran, Bruce T. (2005). Distilling Knowledge: Alchemy, Chemistry, and the Scientific Revolution. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674014952.

- Myers, Richard (2003). The Basics of Chemistry. Greenwood Press. ISBN 0313316643. OCLC 50164580.

- Padilla, Michael J.; Miaoulis, Ioannis; Cyr, Martha (2002). Prentice Hall Science Explorer: Chemical Building Blocks. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey USA: Prentice-Hall, Inc.. ISBN 0-13-054091-9. OCLC 47925884.

- Pauling, Linus (1960). The Nature of the Chemical Bond. Cornell University Press. ISBN 0801403332. OCLC 17518275.

- Pfeffer, Jeremy I.; Nir, Shlomo (2000). Modern Physics: An Introductory Text. Imperial College Press. ISBN 1860942504. OCLC 45900880.

- Ponomarev, Leonid Ivanovich (1993). The Quantum Dice. CRC Press. ISBN 0750302518. OCLC 26853108.

- Scerri, Eric R. (2007). The periodic table: its story and its significance. Oxford University Press US. ISBN 0195305736.

- Shultis, J. Kenneth; Faw, Richard E. (2002). Fundamentals of Nuclear Science and Engineering. CRC Press. ISBN 0824708342. OCLC 123346507.

- Siegfried, Robert (2002). From Elements to Atoms: A History of Chemical Composition. DIANE. ISBN 0871699249. OCLC 186607849.

- Sills, Alan D. (2003). Earth Science the Easy Way. Barron's Educational Series. ISBN 0764121464. OCLC 51543743.

- Smirnov, Boris M. (2003). Physics of Atoms and Ions. Springer. ISBN 038795550X. ISBN 038795550X.

- Teresi, Dick (2003). Lost Discoveries: The Ancient Roots of Modern Science. Simon & Schuster. pp. 213–214. ISBN 074324379X. http://books.google.com/?id=pheL_ubbXD0C&dq.

- Various (2002). Lide, David R.. ed. Handbook of Chemistry & Physics (88th ed.). CRC. ISBN 0849304865. OCLC 179976746. http://www.hbcpnetbase.com/. Retrieved 2008-05-23.

- Woan, Graham (2000). The Cambridge Handbook of Physics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521575079. OCLC 224032426.

- Wurtz, Charles Adolphe (1881). The Atomic Theory. New York: D. Appleton and company. ISBN 055943636X.

- Zaider, Marco; Rossi, Harald H. (2001). Radiation Science for Physicians and Public Health Workers. Springer. ISBN 0306464039. OCLC 44110319.

- Zumdahl, Steven S. (2002). Introductory Chemistry: A Foundation (5th ed.). Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-618-34342-3. OCLC 173081482. http://college.hmco.com/chemistry/intro/zumdahl/intro_chemistry/5e/students/protected/periodictables/pt/pt/pt_ar5.html. Retrieved 2008-02-05.

External links

- Francis, Eden (2002). "Atomic Size". Clackamas Community College. http://dl.clackamas.cc.or.us/ch104-07/atomic_size.htm. Retrieved 2007-01-09.

- Freudenrich, Craig C.. "How Atoms Work". How Stuff Works. http://www.howstuffworks.com/atom.htm. Retrieved 2007-01-09.

- "The Atom". Free High School Science Texts: Physics. Wikibooks. http://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/FHSST_Physics/Atom. Retrieved 2010-07-10.

- Anonymous (2007). "The atom". Science aid+. http://www.scienceaid.co.uk/chemistry/fundamental/atom.html. Retrieved 2010-07-10.—a guide to the atom for teens.

- Anonymous (2006-01-03). "Atoms and Atomic Structure". BBC. http://www.bbc.co.uk/dna/h2g2/A6672963. Retrieved 2007-01-11.

- Various (2006-01-03). "Physics 2000, Table of Contents". University of Colorado. http://www.colorado.edu/physics/2000/index.pl?Type=TOC. Retrieved 2008-01-11.

- Various (2006-02-03). "What does an atom look like?". University of Karlsruhe. http://www.hydrogenlab.de/elektronium/HTML/einleitung_hauptseite_uk.html. Retrieved 2008-05-12.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||

|

|||||